Would you like fries with that?

From the Washington Post

Do you prefer to search for information online with Google or Yahoo? What about bargain shopping -- do you go to Amazon or eBay? Many of us make these kinds of decisions several times a day, based on who knows what -- maybe you don't like bidding, or maybe Google's clean white search page suits you better than Yahoo's colorful clutter.

But the nation's largest telephone companies have a new business plan, and if it comes to pass you may one day discover that Yahoo suddenly responds much faster to your inquiries, overriding your affinity for Google. Or that Amazon's Web site seems sluggish compared with eBay's.

The changes may sound subtle, but make no mistake: The telecommunications companies' proposals have the potential, within just a few years, to alter the flow of commerce and information -- and your personal experience -- on the Internet. For the first time, the companies that own the equipment that delivers the Internet to your office, cubicle, den and dorm room could, for a price, give one company priority on their networks over another.

This represents a break with the commercial meritocracy that has ruled the Internet until now. We've come to expect that the people who own the phone and cable lines remain "neutral," doing nothing to influence the content on your computer screen. And may the best Web site win.

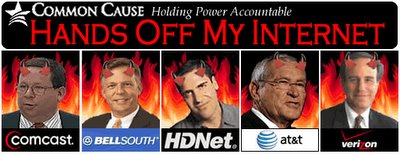

For more than a year, public interest groups, including the Consumer Federation and Consumers Union, have been lobbying Congress and the Federal Communications Commission to write the concept called "network neutrality" into law and regulation. Google and Yahoo have joined their lobbying efforts. And online retailers, Internet travel services, news media and hundreds of other companies that do business on the Web also have a lot at stake.

Meanwhile, on the other side, companies like AT&T, Verizon and BellSouth are lobbying just as hard, saying that they need to find new ways to pay for the expense of building faster, better communication networks. And, they add, because these new networks will compete with those belonging to Comcast, Time Warner and oth er cable companies -- which currently have about

55 percent of the residential broadband market -- this will eventually bring down the price of your high-speed Internet service and television access.

Would these new fees imposed by carriers alter the basic nature of the Internet by putting bumps and detours on the much ballyhooed information superhighway? No, say the telephone companies. Giving priority to a company that pays more, they say, is just offering another tier of service -- like an airline offering business as well as economy class. Network neutrality, they say, is a solution in search of a problem.

Maybe you've never heard of this issue -- and if so, you're far from alone. In my job as a media analyst, I've been talking in recent weeks to lobbyists for some of Hollywood's major entertainment conglomerates. These are people who know that consumers' ability to download their studios' movies and television shows as easily and cheaply as anyone else's will be key to the studios' future profits. Yet hardly any of them were more than vaguely concerned about the potential ramifications of network neutrality.

But lately the issue, a matter of heated debate on obscure blogs and among analysts like me, has begun to attract the attention of the mainstream press. There are a couple of reasons.

One is that Congress is taking first steps toward updating and rewriting the Telecommunications Act of 1996, a key legal underpinning for media, telecommunications and Internet activity. This process, required by technological advances, will probably take a year to complete.

More dramatically, executives at AT&T and BellSouth got into the headlines recently with a series of audacious statements. In a November Business Week story, AT&T Chairman Edward E. Whitacre Jr. complained that Internet content providers were getting a free ride: "They don't have any fiber out there. They don't have any wires. . . . They use my lines for free -- and that's bull," he said. "For a Google or a Yahoo or a Vonage or anybody to expect to use these pipes for free is nuts!''

It was a stunner. Whitacre had apparently declared that AT&T planned to unilaterally abandon its role as a neutral carrier.

Whether or not you agree with Whitacre, you can understand his frustration. Companies like Google and Yahoo pay some fees to connect to their servers to the Internet, but AT&T will collect little if any additional revenue when Yahoo starts offering new features that take up lots of bandwidth on the Internet. When Yahoo's millions of customers download huge blocks of video or play complex video games, AT&T ends up carrying that increased digital traffic without additional financial compensation.

But for public interest advocates, Whitacre's outburst was a Clint Eastwood moment. "Make my day," said Gigi Sohn of Public Knowledge, which focuses on defending consumer rights in the digital world.

Previously, the group had been having trouble convincing members of Congress that there was a network neutrality problem. Legislators and staffers repeatedly had noted to Sohn that no major telephone company had ever used its network to discriminate against other companies. "Whitacre just made the case for regulation," said Sohn. "This was as good as it can get."

Other AT&T executives and spokesmen later said that Whitacre had only been talking about access to a new high-speed broadband network. Industry executives also assured critics that despite Whitacre's bluster, AT&T would never block any Web site, or even degrade the service of a company doing business on the Internet -- even if that service was a voice-over-Internet company such as Vonage, which competes directly with AT&T's core telephone business.

But the blog storm over Whitacre's comments had hardly died down when an executive with BellSouth was quoted saying that the company would consider charging Apple five or 10 cents extra each time a customer downloaded a song using iTunes. Bloggers erupted again, saying that this would certainly drive up the cost of the hugely popular music downloading service.

Google and others say that the prospect of telephone companies imposing new fees on innovative and successful ventures is exactly the kind of thing that deters online commerce. "If carriers are able to control what consumers do on the Internet, that threatens the model of Internet communications that has been wildly successful," said Alan Davidson, Washington policy counsel for Google.

Cable companies abhor the idea of enforced network neutrality just as much as the telephone companies. But so far their executives have remained silent, and stayed out of the crossfire.

The Republican-led Congress is struggling with the issue. On one hand, it has taken a deregulatory approach to the Internet, but on the other, it can't ignore the concerns of Google, Yahoo and eBay, some of the most successful companies of the last 10 years. These companies alone have built up businesses worth hundreds of billions of dollars on an unfettered Internet. Moreover, unfettered Internet access has come to be seen by Americans in general as not just a privilege or a product, but a right akin to free speech and free association.

Over the coming months, the Telecommunications Act will take shape as several different legislative proposals are combined to create a final law. Some of the proposed bills include language on network neutrality, others don't.

The conventional wisdom is that the recent statements by Bell company executives have given network neutrality some momentum. But the bill is not expected to be completed until 2007, leaving lots of time for lobbyists to battle over the strength of the final language.

The FCC, spurred by Commissioner Michael Copps, acknowledged the importance of the issue last October, when it approved two mammoth mergers in the telecommunications industry -- Verizon's $8.5 billion purchase of MCI and SBC Communications' $16 billion purchase of AT&T (SBC quickly assumed the more widely known brand name of AT&T).

One of the few conditions that the FCC put on the merged companies was that they abide by the concept of network neutrality for at least two years. But it's not clear if companies would even be in violation of the relatively vague FCC language if BellSouth or AT&T proceeded with their plan to give one company "priority" over others on the Internet. Last week I asked several telecommunications lawyers, including some FCC staffers, if AT&T would be in violation of its merger agreement if it granted "priority" status to some companies for a fee. The consistent response I got was, "That's a really good question."

At the end of the day, Google's Davidson says that his biggest worry is not for Google but for the prospect of bringing fresh innovation to the Internet. After all, if worse comes to worst, Google can pay AT&T or BellSouth to maintain its role as the Internet's dominant search engine. But the bright young start-up with the next big innovative idea won't have that option.

To read more about the campaign for Network Neutrality go here

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home